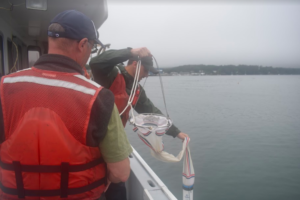

After our first adventure on a research boat studying the Damariscotta River estuary, where we observed how the salinity and mixing state of the estuary affects the diversity of zooplankton and phytoplankton population, we moved on to Rocky Intertidal Zones. We went to Ocean Point at Linekin Neck in Boothbay Harbor, Maine. We completed a transect of the intertidal zone using our previously developed method with a 50-yard tape measure and an inclinometer to determine the slope of the shoreline. The rocky face was covered with many different forms of life, and despite the slippery surface, we found the slopes of each leg of the transect to map the estimated zones of the intertidal.

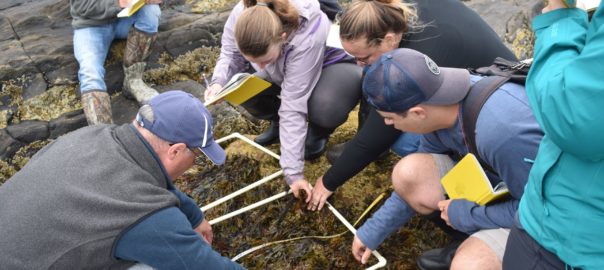

Along the transect, specifically in two-meter intervals, we took flora and fauna surveys of the sessile and motile organisms within the different quardrats we measured. We used a 0.25 m2 quadrat to measure the percent coverage of sessile organisms and a 1 m2 to measure the motile organisms. We found that the physical stresses of the exposed rock, such as the wave shock and desiccation, greatly affect what organisms can live in the exposed area. We found mostly red algae, such as Condrus crispus, right at the low tide line, and many colonies of barnacles towards the middle of the intertidal zone, where there is less exposure, but still great variation of species throughout the tide cycle. From our observations, we concluded that both physical and biological stresses greatly affect the organisms that live in the intertidal zone

After a field day of exciting research, full of wonderment and awe (as Greg would say), we enjoyed a day at the Common Ground Fair. This fair was not your typical rides and games fair, but it was very fun, and they had very good food. After the fair we went out to dinner for Greg’s birthday at Shaw’s Fish and Lobster Rolls, where the view of the harbor at sunset was beautiful. We are all as happy as clams to continue on this trip!

This past week was dedicated to making beach profiles, measuring sediment distributions, determining wave height and energy, all to establish the morphodynamic state of the beaches. We also surveyed the fauna found at high- and low-energy beaches. Although we were staying on the Massachusetts Bay side of Cape Cod, we compared the different energy levels and other morphometric features between the Bay and ocean side beaches of the Cape Cod National Seashore.

This past week was dedicated to making beach profiles, measuring sediment distributions, determining wave height and energy, all to establish the morphodynamic state of the beaches. We also surveyed the fauna found at high- and low-energy beaches. Although we were staying on the Massachusetts Bay side of Cape Cod, we compared the different energy levels and other morphometric features between the Bay and ocean side beaches of the Cape Cod National Seashore.

After a few photos, we continued our journey north to Calais where we crossed the international border into New Brunswick, Canada. From there, we pushed eastward into Saint John, NB to grab a bite to eat before arriving at our destination of Fundy National Park in the late evening.

After a few photos, we continued our journey north to Calais where we crossed the international border into New Brunswick, Canada. From there, we pushed eastward into Saint John, NB to grab a bite to eat before arriving at our destination of Fundy National Park in the late evening. The extent of the boreal forest sits around the northern hemisphere’s subpolar low pressure zone; an area characterized by cloudy skies and lots of precipitation. Amongst the forest was a peat bog. Peat bogs are formed when layers of moss grow upon one another atop stagnant water. The constant moist and low-oxygen conditions prevent decay, allowing new moss to grow on top of old, dead moss, resulting in meters of layered peat. After some time in the forest, we returned to the campground to finish some homework.

The extent of the boreal forest sits around the northern hemisphere’s subpolar low pressure zone; an area characterized by cloudy skies and lots of precipitation. Amongst the forest was a peat bog. Peat bogs are formed when layers of moss grow upon one another atop stagnant water. The constant moist and low-oxygen conditions prevent decay, allowing new moss to grow on top of old, dead moss, resulting in meters of layered peat. After some time in the forest, we returned to the campground to finish some homework. To evaluate the ancient climate, we had to look specifically at the sediments within the layers. The majority of the layers contained large river deposits, suggesting the area was characterized by exceptionally wet, and potentially tropical, conditions. We later learned that the region surrounding Hopewell Rocks was located in the tropical region of an ancient supercontinent around the time these deposits were made, confirming our hypotheses.

To evaluate the ancient climate, we had to look specifically at the sediments within the layers. The majority of the layers contained large river deposits, suggesting the area was characterized by exceptionally wet, and potentially tropical, conditions. We later learned that the region surrounding Hopewell Rocks was located in the tropical region of an ancient supercontinent around the time these deposits were made, confirming our hypotheses.