I am convinced, after studying the writings of the Desert Fathers and Mothers and the medieval mystics, as well as the more contemporary writings of Thomas Merton, John Main, Thomas Keating, and Richard Rohr, that recovering the elements of contemplation is crucial to one’s relationship with others and ultimately one’s unique relationship with Christ. Contemplation in the Christian West, though, was restricted for centuries to within monastery walls, and the resulting polarity of the active and contemplative life has alienated many from the deep prayer “that transcends complexity and restores unity.”[1] Our lives should be a “both, and” rather than an “either, or” – we need action and contemplation. How, though, do we as lay individuals become contemplatives? How do we leave behind our daily distractions and self-piety? How do we enter into the deep prayer of the heart?

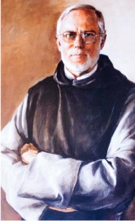

Fr. John Main, OSB (1926-1982) understood, like his contemporary Thomas Merton, that  contemplative prayer provides those answers. We know: God is our creator, Jesus is our redeemer, and the Holy Spirit dwells within us. Nevertheless, do we realize these truths? John Main held that the great weakness of Christians was to know the truths theologically but never obtain living the truths in their hearts.[2] He understood that prayer beyond thoughts and images was a universal calling, and leaning on the teachings of the fourth-century monk, John Cassian, he brought the Christian tradition of using a mantra to the laity through the practice of Christian meditation.

contemplative prayer provides those answers. We know: God is our creator, Jesus is our redeemer, and the Holy Spirit dwells within us. Nevertheless, do we realize these truths? John Main held that the great weakness of Christians was to know the truths theologically but never obtain living the truths in their hearts.[2] He understood that prayer beyond thoughts and images was a universal calling, and leaning on the teachings of the fourth-century monk, John Cassian, he brought the Christian tradition of using a mantra to the laity through the practice of Christian meditation.

“Meditation is the work we do to accept the gift of contemplation which is already given and present in the heart.”[3] However, the term “meditation” in our culture has a variety of meanings. Though meditation is a universal spiritual wisdom, Christian meditation is a form of contemplation (also known as contemplative or meditative prayer) that allows one to experience the fundamental relationship of one’s life – to be in the fullness of one’s  relationship with the Holy Trinity. The old analogy of prayer as a wheel is helpful: the spokes of the wheel are our various expressions of prayer (the Eucharist, the liturgy, the other sacraments, lectio divina, the Rosary, personal devotions, etc.); the hub, the center, is where the spokes converge (the prayer of Jesus in our hearts). Without the hub, without the center, the wheel cannot turn. In the center, in our heart, we find silence, stillness, and simplicity – we find Christ.

relationship with the Holy Trinity. The old analogy of prayer as a wheel is helpful: the spokes of the wheel are our various expressions of prayer (the Eucharist, the liturgy, the other sacraments, lectio divina, the Rosary, personal devotions, etc.); the hub, the center, is where the spokes converge (the prayer of Jesus in our hearts). Without the hub, without the center, the wheel cannot turn. In the center, in our heart, we find silence, stillness, and simplicity – we find Christ.

The silence of meditation follows Matthew’s advice to go to our inner room and pray in silence (Mt 6:5). The stillness of meditation reminds us to live in the world without being subject to it (ref. Mt 6:19-21). The simplicity of meditation helps us set our minds on the Kingdom of God first (ref. Mt 6:25-34). In meditation, one stops thinking about the past or future and lives in the present moment – in the presence of God. Christian meditation revives the meaning of all our expressions of prayer and can influence positively one’s relationships with others.

Thomas Merton, in some of the final words of his life, said, “In prayer we discover what we already have. You start where you are and you deepen what you already have. And you realize that you are already there. We already have everything, but we don’t know it and we don’t experience it. Everything has been given to us in Christ. All we need is to experience what we already possess. The trouble is we aren’t taking time to do so.”[4] Christian meditation is one method to find the necessary center and experience what we already possess.

John Main taught that sitting in silence and stillness and repetitively and silently using a mantra such as maranatha, an Aramaic word meaning, “Come, Lord,” helps us quiet our multitasking minds and truly move our prayer to our hearts. He instructed:

Sit down. Sit still with your back straight. Close your eyes lightly. Then interiorly, silently begin to recite a single word – a prayer word or mantra. We recommend the ancient Christian prayer-word “Maranatha.” Say it as four equal syllables. Breathe normally and give your full attention to the word as you say it, silently, gently, faithfully, and – above all – simply. The essence of meditation is simplicity. Stay with the same word during the whole meditation and in each meditation day to day. Do not visualize but listen to the word, as you say it. Let go of all thoughts (even good thoughts), images, and other words. Do not fight your distractions: let them go by saying your word faithfully, gently and attentively and returning to it as soon as you realize you have stopped saying or it or when your attention wanders. Meditate twice a day, morning, and evening, for between 20 and 30 minutes. It may take a time to develop this discipline and the support of a tradition and community is always helpful.

John Main provided instruction on individual and group Christian meditation showing us how to live a contemplative life within the chaos of our daily lives. His vision for a “monastery without walls” continues with the World Community for Christian Meditation, founded in 1991. In John Main’s words, we pray: Heavenly Father, open our hearts to the silent presence of the spirit of your Son. Lead us into that mysterious silence where your love is revealed to all who call, Maranatha…Come, Lord Jesus.

Fawn Waranauskas teaches spirituality for Saint Joseph’s College.

[1] John Main, OSB, Word into Silence (London: Canterbury Press Norwich, 2006) viii.

[2] Ibid. 5.

[3] Laurence Freeman, OSB, Jesus the Teacher Within (New York: Continuum, 2000) 197.

[4] Pennington, M. Basil, OCSO. Centering Prayer: Renewing an Ancient Christian Prayer Form. (New York: Doubleday, 2001) 49-50.