Saying this, she turned round and saw Jesus standing, but she did now know that it was Jesus. Jesus said to her, “Woman, why are you weeping? Whom do you seek?” Thinking that he was the gardener, she said to him, Sir, if you have carried him away, tell me where you have laid him, and I will take him away.” Jesus said to her, “Mary.” She turned and said to him in Hebrew: “Rabbouni!” (which means teacher). Jesus said to her, “Do not hold on to me, for I have not yet ascended to my brothers and say to them, I am ascending to my Father and your Father, to my God and your God.” Mary of Magdala went and said to the disciples, “I have seen the Lord!” And she told them that he had said these things to her (John 20.14-18).

Few casual readers of the Gospel of John realize that it is rife with riddles, a favorite type of fun for ancient folks. And we all know them even now: “John testified to him and cried out, ‘This was he of whom I said, ‘He who comes after me ranks ahead of me because he was before me.’” Jesus to Nicodemus, “you must be born again!” and to the Samaritan Woman: “I will give you living water to drink.” And perhaps the most famous line and most overlooked riddle: “In the beginning was the Word, and the Word was with God, and the Word was God.”

How can the Word be with and be at the same time? Are the Word and God, in other words, two or one? We are so accustomed to the grandeur, and the received meaning, of the first verse of the Fourth Gospel (4G) that we no longer hear the inherent riddle. Riddles were a popular form of entertainment in the ancient Mediterranean, just as they can be for us today; if we don’t recognize that, we miss a lot of the fun in the 4G.

How can the Word be with and be at the same time? Are the Word and God, in other words, two or one? We are so accustomed to the grandeur, and the received meaning, of the first verse of the Fourth Gospel (4G) that we no longer hear the inherent riddle. Riddles were a popular form of entertainment in the ancient Mediterranean, just as they can be for us today; if we don’t recognize that, we miss a lot of the fun in the 4G.

The 4G relishes the use of riddles, much as the synoptic gospels use parables (of which there are none in the 4G), to “reward” the reader who already “gets it” and to help the readers who don’t see the world around them in a new way. Not only is the wordplay unfortunately and unavoidably often lost in the English translation, the irony is often lost on those who want an either/or answer: to “get it,” one must often be open to a “both/and” solution. The joy is that the riddles themselves, like parables, are designed to help one open us to a new way of seeing the world, often one that is less either/or than both/and.

While most readers pick up on the creation references at the beginning of the 4G, may miss the use of creation symbolism at the end. We begin the end, so to speak, with the creation motif and the final (7th) sign: the resuscitation of Lazarus (11.1-44), again emphasizing the theme of acts of creation, of giving life. Jesus’ resurrection could be counted as an eighth sign, foreshadowed in the seventh and beginning the time of renewed creation. In the 4G, however, the crucifixion and resurrection are one moment, as it were, indicating renewed creation.

That context lies in the background of the 4G’s narration of Jesus’ death on the cross, which is distinct from that of the synoptic gospels. Jesus’ final words here are “It is finished” (19.30), placed to repeat the narrator’s assertion in v. 28, “when Jesus knew that all was now finished” (teleo). The Greek word translated “finished” is best understood not as “ended” but as “brought to completion” or “fulfilled,” and just after Jesus dies, we read immediately that the Sabbath is about to begin (19.31). Jesus’ doing the Father’s work of bringing “life” as he completes stages of that work (see 4.34 and 5.36) and fulfilling it by his voluntary offering of his life “for his friends” ushers in the Sabbath renewal.

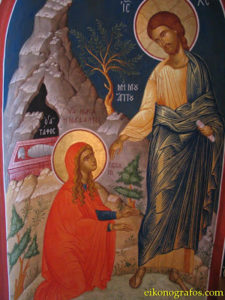

This new creation is underlined again in 20.1 as the resurrection narrative begins: “Early on the first day of the week [sabbaton].” The garden setting of the resurrection appearance to Mary of Magdala, like the “in the beginning” and other symbols that open the 4G, points us back to Genesis. When Mary mistakes Jesus for the gardener, and that’s a both/and: she is literally wrong but spiritually correct, and that points in itself to a symbolic meaning: the portrayal of Jesus as the new Adam, a motif present in other early Christian literature. Jesus is the Word, fulfilling the creation, and is also the new Adam, ushering in a new human participation in that creation. It’s then a short step to think of the Creator God of the garden, the earth.

Mary’s own awareness comes when she hears the voice of her shepherd speak her name (recalling Jn 10.3). This scene is, without a doubt, one of the most intimate scenes of the Bible that can lead each Christian to ask: by what name does Jesus address me? How do I know Jesus’ voice? And in her great love, Mary does what all of us do: she tries to hold on, to freeze the happy moment in space and time. (“Touch” is a very poor translation.) But Jesus instructs her not to hold on to this experience: she is to be open to the new experience of Jesus not physically present but freed from the bounds of space and time and so always present in eternal life now in the context of the entire creation, permeating the whole cosmos. The encounter between the risen Jesus and Mary is clearly a message to and by the community: do not only look back at the so-called “historical” Jesus, but be aware of his constant presence now in each other as you live and breathe in the universe. Be aware of the eternal and life-giving presence of the Gardener.

Pamela Hedrick teaches Sacred Scripture for Saint Joseph’s College Online.