Recently, the Vaticanisto Sandro Magister published a letter sent to him by an Italian professor-priest who, despite his academic activity, dedicates a significant amount of time to pastoral work. While the letter addresses somewhat larger issues, what I found particularly significant is the following observation the author makes concerning the Jubilee Year of Mercy and the sacrament of Confession.

The facts are these. Since the opening of the Holy Year backed by Pope Francis and on the occasion of the Christmas festivities of 2015 – as also since Jorge Mario Bergoglio has been sitting on the throne of Peter – the number of faithful who approach the confessional has not increased, neither in ordinary time nor in festive. The trend of a progressive, rapid diminution of the frequency of sacramental reconciliation that has characterized recent decades has not stopped. On the contrary: the confessionals of my church have been largely deserted.

Despite the anecdotal nature of this observation, I have a sneaking suspicion that it rings true throughout much of the Church in Europe and North America. And while it may come as no surprise to many, I am nonetheless saddened to hear it.

By declaring this liturgical year a Jubilee of Mercy, Pope Francis is attempting to place front and center the very core of Jesus’ own preaching message. At the beginning of his earthly ministry, Jesus proclaimed: “This is the time of fulfillment. The kingdom of God is at hand. Repent (metanoeite), and believe in the Gospel (evangelio)” (Mk 1:15; cf. Mt 4:17). The word which is often translated as ‘repent,’ more literally means ‘change your mind.’ Jesus’ message is a call to conversion, an invitation to accept God’s abounding mercy into one’s heart, soul, and mind (cf. Mt 22:37; Dt 6:5); dying to sin and living a new life in the Spirit (cf. Rom 6:11; 8:10). God had frequently proclaimed this call to repentance to ancient Israel through her prophets. As the psalmist writes, “Oh, that today you would hear his voice: do not harden your heart” (95:7-8). But in the person of Jesus, God’s mercy has taken on human form.

The Latin word for ‘mercy’ (misericordia) contains within it the word ‘heart’ (cordis). To be merciful is to share in the ‘heavy’ (miseria, misery) heart of another. In this regard, God’s mercy is made flesh in the incarnation of His Son; who entered into a fallen world, i.e., “became sin” (2 Cor 5:21), for the sake of our salvation. In Christ, God has taken on our ‘heavy hearts’ in a unique and definitive way. Thus, as the letter to the Hebrews states, “we do not have a high priest who is unable to sympathize with our weaknesses, but one who has similarly been tested in every way, yet without sin. So let us confidently approach the throne of grace to receive mercy” (Heb 4:15-6). This is indeed ‘good news’ (evangelion)!

In synoptic gospels most especially, it is clear that Jesus’ mission is one of healing and  forgiveness. Again, at the beginning of his earthly ministry, Jesus proclaims that he “did not come to call the righteous but sinners” (Mk 2:17), and Jesus’ capacity to forgive sins is a sign of his divine authority (cf. Mt 9:6). This ministry of mercy is one that he enjoined to his apostles (cf. Mk 3:15; 6:7; Mt 18:18); they were to participate in Jesus’ own ministry of healing and forgiveness (cf. Jn 20:21-23). Only God can forgive sins, and this ‘capacity’ (potestas) to forgive sins comes not from priests, or bishops, or even the apostles themselves, but from God’s “Word made flesh” (Jn 1:14), Jesus Christ.

forgiveness. Again, at the beginning of his earthly ministry, Jesus proclaims that he “did not come to call the righteous but sinners” (Mk 2:17), and Jesus’ capacity to forgive sins is a sign of his divine authority (cf. Mt 9:6). This ministry of mercy is one that he enjoined to his apostles (cf. Mk 3:15; 6:7; Mt 18:18); they were to participate in Jesus’ own ministry of healing and forgiveness (cf. Jn 20:21-23). Only God can forgive sins, and this ‘capacity’ (potestas) to forgive sins comes not from priests, or bishops, or even the apostles themselves, but from God’s “Word made flesh” (Jn 1:14), Jesus Christ.

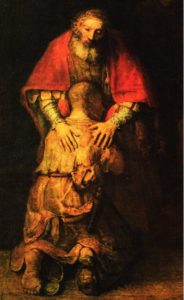

And so, when the Church, Christ’s body (1 Cor 12:27), forgives sins through her ministers, she is participating in Christ’s own ministry and has done so throughout the ages. What we Catholics call the sacrament of Confession or Penance or Reconciliation, is an extension of various scenes contained throughout the New Testament of Christ forgiving the sinner: the woman caught in adultery (Jn 8:1-11), the paralytic – lowered down from the open roof of a house (Mk 2:5, 9), and the ‘sinful woman’ who bathes Jesus’ feet with her penitential tears (Lk 7:48).This mercy, Jesus’ own, is offered to us every time we visit in the confessional.

Often, we view the sacrament of Reconciliation as a “duty” or, even worse, as something

superfluous. It is no more a duty than it would be to seek Jesus’ forgiveness if he were standing right here before you. It is no more superfluous than it was for the adulterer, or the paralytic, or the sinful woman. Rather, the sacrament of Reconciliation is supreme gift. Through it, and the other sacraments, Jesus fulfills his promise to be with us “until the end of the age” (Mt 28:20). In fact, in the confessional, the mercy of God is being offered exactly as if Jesus were standing right here before you.

Thus, for this Year of Mercy, what’s more important than visiting a ‘holy door’ – with all due respect to those involved in this activity – is to visit the ‘holy door’ of the confessional. In the sacrament of Reconciliation, you have an opportunity to visit Jesus. Make that your first stop before visiting his house.

Anthony Coleman teaches theology for Saint Joseph’s College Online.